Building an Evaluative Mindset at Hallam #4: Evaluation Design

At this stage, evaluators should have agreed the purpose of the evaluation and demonstrated what they are trying to achieve and how the initiative will address the issue. This fourth blog post focuses on the design of the evaluation, which relates to the credibility and reliability of evidence of impact. The blog post will explore five key steps for effective evaluation research, as identified by Parsons (2017), which STEER promote for all evaluative work.

Evaluation research is not incremental. It requires clarity of expectations and needs before all else.

Parsons (2017) states that unrealistic expectations can arise from a lack of clarity and coherency in the evaluation’s rationale, objectives, use of findings and resourcing. The danger of not challenging unrealistic expectations from the beginning could be costly to an evaluation, for example, by not meeting the expectations of stakeholders (see Figure 1) or producing evidence that is unsuitable for its intended purpose. One useful source to help with effective design is the Roles-Outcomes-Timing-Use-Resourcing (ROTUR) framework.

ROTUR framework (Parsons, 2017)

The framework outlines the ‘do’s and don’ts’ of evaluation planning and enables realistic expectations to be set about what the evaluation is trying to achieve, why it is needed, who it will be carried out by and for when:

- Roles that are clear and appropriate, such as identifying who the end users are and who is responsible for specification.

- Outcomes expected of the evaluation, such as whether the objectives are clear and consistent with the rationale and evidence that can be gathered.

- Timing and delivery which is appropriate, for example, factoring in time with stakeholders and for data collection and reviewing.

- Use and clarity for users, such as determining how findings will be used and how primary, secondary and non-users will be engaged.

- Resourcing that is fit for purpose, such as having appropriate funding, time, expertise, access to data and project management skills needed for the evaluation.

One size does not fit all: Good evaluation research design is always customised to some extent.

The unique nature of each initiative and evaluation means that the design will always need to be tailored around several issues such as: the evaluation questions and its purpose (Better Evaluation); the methods and procedure; the nature of the relationship with stakeholders; and the resources that are available.

Effective design is not just about methods: It needs to combine technical choices (contextualised, fit for purpose and robust) with political context (so it is understood, credible and practical)

The role of politics, cultural factors and relationships in the evaluation design must not be underestimated. As evaluations can have a potentially negative impact on stakeholders, it is pivotal to ‘build the trust required to convince the people who will feel the consequences’ (Lysy, n.d.):

- Decisions about the evaluation should not be driven by any ‘unacknowledged and self-serving agendas’ (Rogers, Hawkins, McDonald, Macfarlan & Milne, 2015, p. 52) but by existing key stakeholders and evidence, which can be drawn upon to challenge assertions and assumptions.

- Determining the focus of an evaluation is in itself a political task as it involves prioritising the interests and needs of certain groups over others and the decision-making process requires transparency (Buffardi & Pasanen, 2016).

- Parsons (2017) identified four principles from the literature that relate to ethics in evaluation, which consists of: avoiding harm; providing fairness in evidence gathering and interpretation; ensuring independence across the process; and providing appropriate communication of findings and implications.

- Evaluators may face pressure to demonstrate impact and focus on what is working but this should be balanced by the need to learn and explore what aspects are not working optimally. Furthermore, unintended consequences need to be included within the scope of the evaluation, which includes engaging with ‘diverse informants’ (Rogers et al., 2015).

Participatory evaluation

Participatory evaluation has the capacity to empower beneficiaries of an initiative by involving them as co-evaluators in all or specific parts of the process (Better Evaluation, 2020). This can add credibility, allow ‘hidden’ perspectives to be explored and help to maximise adoption of findings and recommendations (Parsons, 2017). However, participation needs to go beyond methods and individuals need to be heard and responded to in order to avoid tokenistic participation (Groves & Guijt, 2015; Participatory methods), which means doing much more than just distributing a survey (see Figure 2).

Good design is always proportionate to needs, circumstance and resources

The focus is on ensuring that the evaluation design is robust relative to the purpose and scale of the evaluation and the resources that are available (Parsons, 2017). This stance is reflected in the Office for Students’ non-hierarchical standards of evidence, which is comprised of three levels: narrative (type 1), empirical (type 2) and causal (type 3). The aim of the following guidance from the sector is to complement existing information by the Centre for Social Mobility (2019b):

- In the context of new models or poorly-evidenced programmes, the evaluation should focus on processes and adopt a staged-process (Harrison-Evans, Kazimirski, & McLeod, 2016), for example: undertaking a needs assessment to determine if the initiative is necessary; establishing its principles and the underpinning logic of activities using existing evidence; and modifying its design in response to emerging feedback. This would represent a narrative (type 1) standard (Centre for Social Mobility, 2019a).

- In the case of more established initiatives, data should be collected on the outcomes and impact, which focuses the standard of the evaluation at an empirical (type 2) level at the very least. Evaluators need to consider: how changes in participants will be measured, such as by capturing baseline data and tracking participants over time; using a mix of methods and sources; and using inferential statistical analysis to go beyond description (Centre for Social Mobility, 2019b; Harrison, Vigurs, Crockford, McCaig, Squire & Clark, 2018).

- The counterfactual perspective (i.e. what would have happened if an initiative had not taken place) must be considered to meet the requirements of a robust empirical or causal standard. There are different ways of generating counterfactual evidence, each of which has varying levels of confidence and threats to the validity of their findings (Better Evaluation, 2013).

- An experimental design is considered to be the most robust counterfactual evidence by establishing cause and effect (type 3) and accounting for observable and unobservable differences between participants and a control group and through random selection (see TASO, who have provided a useful example for differentiating between empirical and causal standards). However, these designs might be impractical in many ‘messy real-life settings’ (Bellaera, 2018).

- If this is not possible, a quasi-experimental design is a flexible alternative where the outcomes of participants are compared against a closely-matched comparison group who did not receive the intervention (see Figure 3 for an example of bad practice with glaring differences).

- Non-experimental designs, considered to be less robust as findings are correlational and extraneous variables cannot be controlled, involve tracking the outcomes of participants (for example, in a pre/post design) and estimating what would have happened without the intervention, such as by using key informants.

- ‘More intensive and costly interventions usually require higher standards of evidence’ (Centre for Social Mobility, 2019b, p. 18), for example, demonstrating a causal relationship (type 3) is a more realistic expectation for high-profile and large-scale interventions compared to a one-off initiative.

Case study: Student Perceptions of Learning Gain (Jones-Devitt et al., 2019)

As part of STEER’s evaluation of the National Mixed Methods Learning Gain Project, which was conducted on behalf of the Office for Students, the second phase of research explored student perceptions of learning gain. Focus groups were carried out with students from institutions who participated in the learning gain project. To increase robustness of this phase, a counterfactual process was implemented by ascertaining the views of students within an institution where the project had not taken place. This is an example of an empirical (type 2) standard of evaluation.

Method choices are led by a primary dichotomy: consideration of measurement (how much) vs. understanding (how; why). The chosen method can do both, if required.

Using a combination of methods, which Parsons (2017) referred to as a hybrid design, can be more informative than using individual methods in isolation (e.g. the McNamara Fallacy) as evidence is triangulated. There is greater confidence in the findings and less opportunity for findings to be misinterpreted or manipulated (Rodgers et al., 2015). There is growing recognition for the need to use qualitative methods to provide evidence of context, experience and meaning alongside quantitative methods:

- Reflective practice captures the perspectives of practitioners as key stakeholders by encouraging them to reflect and record their experiences, thereby generating context-specific information and engaging them in a process of continuous learning (Participatory methods). Beyond organisational learning and evaluation, reflective practice is also commonly used to explore topics such as power and relationships.

- The Financial support evaluation toolkit, which consists of tools for undertaking a statistical analysis, a survey and an interview, helps institutions examine the relationship between financial support and key student outcomes, such as degree attainment, and provide insight into how and why the support works (see McCaig et al., 2016).

- HeppSY is a Widening Participation programme in South Yorkshire that adopts a realist evaluation approach in order to take into account the contextual factors that might prevent young people from accessing higher education (Pawson & Tilley, 1997). Data is collected using multiple sources (e.g. students, parents and school staff), self-report (e.g. surveys), qualitative (e.g. interviews and focus groups) and objective measures (e.g. Higher Education Access Tracker).

- Better Evaluation (2013) has provided a comprehensive list of data collection methods that have been clustered into five groups: information from individuals; information from groups; observation; physical measurements; and reviewing existing data. Another useful resource for exploring content on methods is the SAGE methods map.

- An evaluation matrix can help users determine if there are sufficient data sources to answer each key question within the evaluation (Better Evaluation).

Creative methods offer a compelling alternative for individuals who may not wish to engage with tried, tested but potentially tired methods, such as questionnaires. Sensitive and complex topics can be easier to discuss using approaches that promote interaction and participation. Examples of creative methods in practice include the following:

- Digital storytelling has emerged as an innovative methodology in educational research at Sheffield Hallam (see Austen & Jones-Devitt, 2018) and across the sector (e.g. Sherwood, 2019) for instigating behavioural change, capturing personal stories and giving voice to individuals who are often marginalised.

- Listening Rooms has been developed at Sheffield Hallam as a methodology that utilises student friendships to elicit understandings of students’ journeys (Heron, 2020).

Body mapping exercises are appropriate for exploring perceptions of individuals and groups and providing evidence of unexpected outcomes. A range of other creative methods, with accompanying guidance and templates, have been provided by Evaluation Support Scotland, for example: journey maps, evaluation wheels and tools for capturing non-formal responses. - There are many examples of approaches which do not require in-person engagement, which present opportunities for activities to continue during a pandemic (e.g. Lupton, 2020) if deemed appropriate (Ravitch, 2020). For example, social media platforms, such as Twitter and Instagram, are used to record and share comments and useful guidance has been produced by Iriss (2015) and Townsend and Wallace (2016).

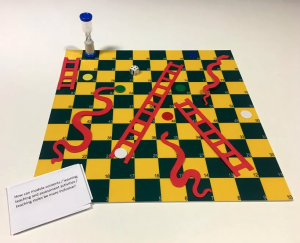

Case study: Snakes and ladders ‘with a difference’ (Jones-Devitt, 2013)

In this adapted game of snakes and ladders, participants are presented with pedagogic scenarios and asked to make critical and collective decisions about what each moveable ladder and snake represent. In the context of the Class of 2020 project, one workshop used this method:

- Students were asked to identify three enablers of belonging, represented by the ladders, and three inhibiting factors, represented by the snakes.

- Upon landing on a snake or a ladder, the participant is tasked with answering a pre-populated task card, which contained a question about belonging and identity that was linked to themes from sector-wide evidence.

- The rest of the group must form a consensus view to determine whether the participant has earned the right to stay or move, as judged by the quality of their response.

‘Drowning in data’? Help is at hand

Copious amounts of data are collected across institutions but it does not speak for itself. Skills in interpreting and analysing this data are necessary to help diagnose issues and to determine the impact of work. However, the task of ‘making sense’ of evidence and evaluation should be a supportive, rather than a scary, process through a culture of continuous improvement and capacity building:

- There must be an understanding that individuals and groups will be at different positions in their ‘quest’ to achieve more robust forms of evaluation and this process of enhancement will take place over time.

- The creation of a local ‘evaluation repository’ will collate examples of good practice and ‘lessons learnt’ from institutional evaluations, which will be assessed in line with OfS standards and provide an evidence base to inform future evaluation design. This will complement the recently-launched toolkit by TASO.

- Engagement with workshops and events by STEER and sector-wide conferences (e.g. Why Evaluate?), hubs and networks (e.g. TASO and National Education Opportunities Network) and communities of practice (e.g. Making a Difference with Data and EvalCentral) can provide further ideas and guidance about evaluation design and processes.

References and Further Reading

Austen, L. & Jones-Devitt , S. (2018) Observing the observers: Using digital storytelling for organisational development concerning ‘critical Whiteness’. AdvanceHE. https://www.lfhe.ac.uk/en/research-resources/research-hub/smalldevelopment-projects/sdp2018/sheffield-hallam-university-po.cfm .

Bellaera, L. (2018, January 18). We need realistic evaluations of HE access. Wonkhe. https://wonkhe.com/blogs/we-need-realistic-evaluations-of-he-access/

Better Evaluation. (n.d.). Compare results to the counterfactual. https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/rainbow_framework/understand_causes/compare_results_to_counterfactual

Better Evaluation. (n.d.). Participatory Evaluation. https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/plan/approach/participatory_evaluation

Better Evaluation. (n.d.). Guidance on choosing methods and processes. https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/start_here/which_method_or_process#Matrix

Better Evaluation. (2013).Describe activities outcomes, impacts and contexts: https://www.betterevaluation.org/sites/default/files/Describe%20-%20Compact.pdf

Better Evaluation. (2016). Specify the Key Evaluation Questions. https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/rainbow_framework/frame/specify_key_evaluation_questions

Buffardi, A. & Pasanen, T. (2016, June 14). Measuring development impact isn’t just technical, it’s political. ODI. https://www.odi.org/blogs/10412-measuring-development-impact-isnt-just-technical-its-political

Centre for Social Mobility (2019a). Access and participation standards of evidence. h https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/media/6971cf8f-985b-4c67-8ee2-4c99e53c4ea2/access-and-participation-standards-of-evidence.pdf

Centre for Social Mobility (2019b). Using standards of evidence to evaluate impact of outreach. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/media/f2424bc6-38d5-446c-881e-f4f54b73c2bc/using-standards-of-evidence-to-evaluate-impact-of-outreach.pdf

Evaluation Support Scotland. (n.d.). Evaluation Methods and Tools. https://www.evaluationsupportscotland.org.uk/resources/ess-resources/ess-evaluation-methods-and-tools/

Geckoboard. (n.d.). McNamara Fallacy. https://www.geckoboard.com/uploads/mcnamara-fallacy.pdf

Groves, L. & Guijt, I. (2015, July 15). Positioning participation on the power spectrum. Better Evaluation. https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/blog/positioning_participation_on_the_power_spectrum

Harrison, N., Vigurs, K., Crockford, J., Colin, M., Squire, R., & Clark, L. (2018). Evaluation of outreach interventions for under 16 year olds: Tools and guidance for higher education providers. https://derby.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10545/623228/Published%20Tools%20-%20OFS%202018_apevaluation.pdf?sequence=1

Harrison-Evans, P., Kazimirski, A., & McLeod, R. (2016). Balancing act: A guide to proportionate evaluation. NPC. https://www.thinknpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Balancing-act_A-guide-to-proportionate-evaluation_Final.pdf

Heron, E. (2020). Friendship as method: reflections on a new approach to understanding student experiences in higher education. Journal of further and higher education, 44(3), 393-407.

heppSY. (n.d.). Evaluation & Data. https://extra.shu.ac.uk/heppsy/schools/dataandevaluation/

Jones-Devitt, S. (2013) Performing critical thinking? Chapter in edited book in conjunction with Association of National Teaching Fellows, showcasing excellence in teaching in T. Bilham (Ed.) For the Love of Learning: innovations from outstanding university teachers Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.

Jones-Devitt, S., Pickering, N., Austen, L., Donnelly, A., Adesola, J., & Weston, A. (2019). Evaluation of the National Mixed Methods Learning Gain Project (NMMLGP) and Student Perceptions of Learning Gain.

Lupton, D (Ed.). (2020). Doing fieldwork in a pandemic (crowd-sourced document). https://docs.google.com/document/d/1clGjGABB2h2qbduTgfqribHmog9B6P0NvMgVuiHZCl8/mobilebasic

McCaig, Colin, N. Harrison, A. Mountford-Zimdars, D. Moore, U. Maylor, J. Stevenson, H. Ertle, & H. Carasso. (2016). Closing the Gap: Understanding the Impact of Institutional Financial Support on Student Success. Office for Fair Access. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20180511112320/https://www.offa.org.uk/egp/impact-of-financial-support/

Narrowing The Gaps. (n.d.). Listening Rooms. https://blogs.shu.ac.uk/narrowingthegaps/listening-rooms/?doing_wp_cron=1589376503.5882511138916015625000

Office for Students. (n.d.). Financial support evaluation toolkit. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/promoting-equal-opportunities/evaluation/financial-support-evaluation-toolkit/

Parsons, D. (2017). Demystifying evaluation: Practical approaches for researchers and users. Policy Press.

Participatory Methods. (n.d.). Levels of Participation. https://www.participatorymethods.org/method/levels-participation

Participatory Methods. (n.d.). Reflective Practice. https://www.participatorymethods.org/method/reflective-practice

Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. SAGE..

Rogers, P., Hawkins, A., McDonald, B., Macfarlan, A., & Milne, C. (2015). Choosing appropriate designs and methods for impact evaluation. Office of the Chief Economist, Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, Australian Government. https://www.industry.gov.au/sites/default/files/May%202018/document/pdf/choosing_appropriate_designs_and_methods_for_impact_evaluation_2015.pdf?acsf_files_redirect

SAGE. (n.d.). Methods Map: https://methods.sagepub.com/methods-map

Student Engagement Evaluation and Research. (n.d.). Digital Storytelling @ SHU. https://blogs.shu.ac.uk/steer/digital-storytelling-shu/?doing_wp_cron=1610190869.3672370910644531250000

TASO. (n.d.). Evidence toolkit. https://taso.org.uk/evidence/toolkit/

Townsend, L. & Wallace. C. (n.d.). Social Media Research: A Guide to Ethics. https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_487729_smxx.pdf

close