Making Learning Meaningful: Reflections on a Pedagogy of Kindness, Belonging and Play

In higher education, learning is often discussed in terms of outcomes. Success is measured through grades, progression, satisfaction scores, and employability metrics. These matter. Yet, in my experience, learning only becomes truly meaningful when something more fundamental is in place: when students feel that they belong and that they matter.

This has felt especially visible in my classrooms over the past year. Many of my students are navigating cultural transition, language anxiety, disrupted study pathways, or the quiet pressure of trying to fit in. When students feel invisible or unsafe, participation narrows, confidence shrinks, and learning becomes something to endure rather than something to inhabit.

Over the past year, I have been intentionally developing my teaching around a pedagogy of kindness. I understand kindness here not as a personal trait, but as a pedagogical stance. It involves deliberate decisions about how learning spaces are designed, how relationships are built, and how students are positioned within the classroom. What I have observed is deeper engagement, growing confidence, and learning environments that feel genuinely meaningful for both students and myself.

What kindness looks like in practice

Kindness in teaching shows up through everyday practices. It is present in what I choose to acknowledge, how I respond to students, and the behaviours I model. It is sometimes misunderstood as lowering standards or avoiding challenge. In my practice, I have found the opposite. When kindness is designed into learning, it creates the conditions for intellectual risk-taking, confidence, and sustained engagement.

One place this begins is through role modelling.

In a postgraduate international business class, I intentionally acknowledged the Indian festival of Diwali (the festival of light) through a dedicated slide in my lecture materials. I also brought chocolates to share with the group, keeping with the tradition. This was a small, deliberate pedagogical act, but its impact was immediate. It signalled to students that their cultural identities were noticed, valued, and welcome in the learning space.

In the weeks that followed, students began bringing items to share themselves. Acts of kindness started to circulate organically around the room. These moments did more than create a pleasant atmosphere. They strengthened a sense of belonging and mattering. Students were no longer simply present in the classroom; they became invested in it. Care had been modelled through my teaching practice, and it was returned through peer-to-peer generosity, creating a shared learning community.

Figure 1: Tutor with students

I saw similar effects in my Level 6 undergraduate International Business module, made up of Sheffield Hallam University students and European exchange students. Through consistent modelling of kindness, care, and joy in the classroom, students described an environment that felt welcoming, motivating, and human. Several shared unsolicited feedback through emails and handwritten cards, reflecting on how this atmosphere positively shaped their experience of the module. For some, it eased the transition back from placement, helping them rebuild confidence, reconnect with peers, and re-engage with learning.

Kindness has also involved appropriate vulnerability in my teaching. I shared parts of my own story as a former international student, including moments of uncertainty, isolation, and adjustment. I noticed how this helped students relax and recognise elements of their own experiences.

One student, in particular, never spoke during early sessions. She always relied on a peer to speak on her behalf. Rather than forcing participation, I spent time sitting with her during group tasks, talking through ideas, and checking in after class. Gradually, she began to speak independently. Over time, her confidence grew, and I began to see just how thoughtful and analytical her contributions were. This shift did not come from assessment pressure, but from feeling seen.

Play as a learning resource

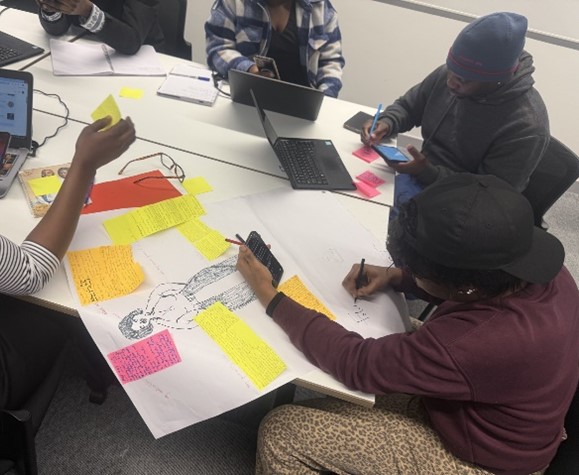

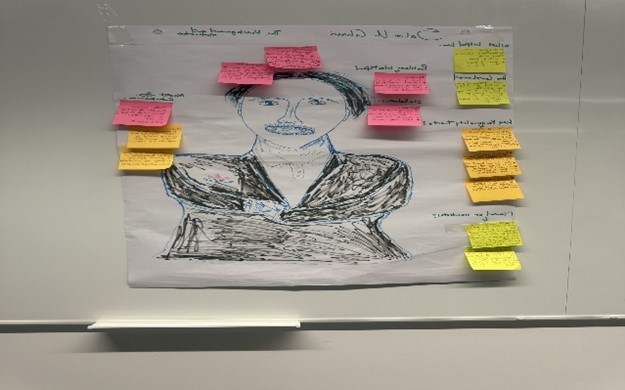

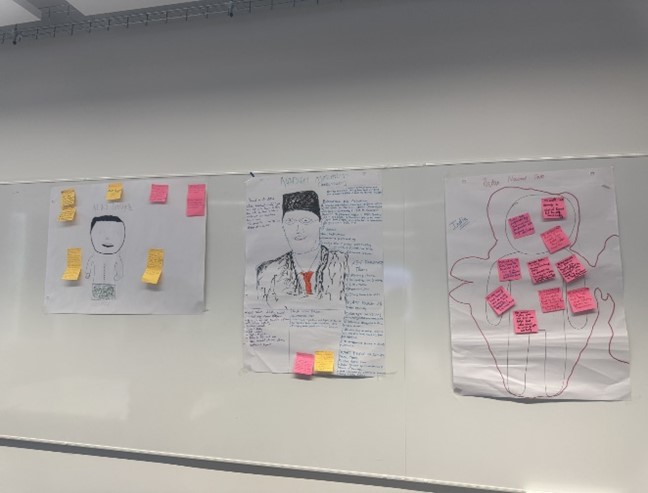

Kindness in my pedagogy is closely connected to play. Play creates space for curiosity, expression, and shared meaning-making. In a postgraduate seminar on international entrepreneurship, I asked students to identify entrepreneurs they knew. Global figures dominated the list. Through discussion and a playful, creative task using drawings, music, and group research, students began identifying entrepreneurs from their own countries. The room lit up. Students laughed warmly at one another’s drawings, debated ideas, and shared stories. That laughter mattered. It eased anxiety, strengthened connection, and opened space for learning that felt alive. When the session ended, students stayed. They asked to continue beyond the allocated time. Several later told me they were attending classes not because of attendance monitoring, but because they wanted to be there.

Figures 5-7: Seminar Activity: Using ART and PLAY as technique for exploring real entrepreneurial journeys

Why this matters for Teaching and Learning

Belonging and mattering shape whether students speak, persist, and engage. Belonging is experienced through acceptance, while mattering is felt through being noticed, valued, and able to contribute meaningfully. A pedagogy of kindness supports this process by treating students as whole people and designing learning spaces around recognition, reciprocity, and shared meaning. It creates classrooms where intellectual challenge sits alongside emotional safety, enabling rigorous and meaningful learning. For those engaged in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, this raises an important question: What kinds of classrooms are we designing, and who do they allow to flourish?

For me, this has reinforced a simple but powerful insight. A pedagogy of kindness does not dilute academic standards. It shapes the conditions under which rigorous, meaningful learning becomes possible; where students feel they belong, and where they know they matter.

References

Baumeister, R. F. and Leary, M. R. (1995) The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), pp. 497–529.

Broidy, S. (2019) A Case for Kindness: A New Look at the Teaching Ethic. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Denial, C. J. (2019) A Pedagogy of Kindness. Hybrid Pedagogy.

Elliott, G. C., Kao, S. and Grant, A. M. (2004) ‘Mattering: Empirical validation of a social-psychological concept’. Self and Identity, 3(4), pp. 339–354.

Prilleltensky, I. (2020) ‘Mattering at the intersection of psychology, philosophy, and politics’. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(1–2), pp. 16–34.

Schlossberg, N. K. (1989) ‘Marginality and mattering: Key issues in building community’. New Directions for Student Services, 48, pp. 5–15.

Thomas, L. (2012) Building student engagement and belonging in higher education at a time of change. London: Paul Hamlyn Foundation.

Zawada, C. (2024) ‘Student dropout and feelings of belonging and mattering in UK undergraduate students’. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, 31.

Author

Dr Caroline Kom, Senior Lecturer in International Business